The meaning changes depending on the processors, of which I include a few examples below. I think that because of the concept of forward compatibility, once a WORD was given a size (say 16 bits), it stayed that way for the whole series of those processors. Note that some processors started as 32 bits and still had a WORD of 16 bits (see 68000). So, more or less, you have to read that processor's documentation to find out the size of a WORD and as a result there is no exact definition that would apply to all processors.

As pointed out by Peter Cordes, the word is also used in other places such as C/C++ and there they can really mean anything. In this strlen() post, the comment says:

/* All these elucidatory comments refer to 4-byte longwords,

but the theory applies equally well to 8-byte longwords. */

in which case, we could say that the term "longword" refers to the architecture general register size of 32 or 64 bits.

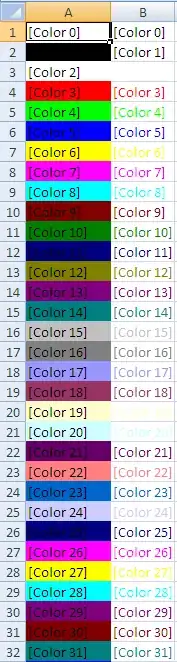

Intel/AMD Processors

For the Intel family of CPUs a WORD is 16 bits, even though those CPUs now support up to 512 bits registers (with AVX512, see the ZMM registers).

The operands of these instructions are packed integers of byte, word, or double word sizes. The operands are stored as 64 or 128 bit data in MMX registers, XMM registers, or memory. (Vol 1. 12.6 SSSE3 INSTRUCTIONS)

This has been the case from the 8086 since at that time registers were 16 bits. The meaning has not changed (see 4.1 FUNDAMENTAL DATA TYPES).

- Byte -- 8 bits

- Word -- 16 bits

- Double Word -- 32 bits (often abbreviated DWord)

- Quadword -- 64 bits (often abbreviated QWord)

- Double Quadword -- 128 bits (see 4.1.1 Alignment of Words, Doublewords, Quadwords, and Double Quadwords)

I think many older processors use WORD to mean 16 bits. If you're using Intel / AMD or similar processors, for sure, a WORD is 16 bits and I don't think it's going to change.

68000 Processor

This process uses a WORD of 16 bits as well, even though it is also a 32 bit processor (and there were no 16 bits version).

- Byte -- 8 bits

- Word -- 16 bits

- Longword -- 32 bits

ARM Processor

Here is the list of data types for the ARM processor and it is different. A word is 32 bits. Yet newer processors are 64 bits.

Again, I think that comes from the fact that they did not want to change the terminology for their users could get really confused if it changed just because a processor becomes more powerful.

R5000 (Risc)

These newer MIPS processors are also 64 bits processors. Yet a WORD is only 32 bits. Again, probably to maintain compatibility with older 32 bit versions of the processor.

CUDA

The CUDA processors use a WORD of 32 bits. I did not find the definition of data types, but found this section where they reference a half-word as being 16 bits. They also have a byte (8 bits). Again, this CPU supports 64 bits and has been for a while.

SPARC

I could not find a clear list of types in the documentation I have, but there is this clear reference which defines a half-word as 16 bits.

- half-word -- 16 bits

- word -- 32 bits

- double word -- 64 bits

CRAY-1

The CRAY computers used 64 bits CPUs from day one. As a result, their word is 64 bits.

COMPUTATION SECTION

- 64-bit word

- 12.5 nanosecond clock period

- 2's complement arithmetic

- ...