All x86 cpu's have Instruction pointer register which holds the offset (address) of next instruction to be fetched for execution. Providing there is no branching or jumps what is the typical amount which is incremented (or decremented) for the next instruction to fetch? I would think it would be the size of a typical instruction perhaps 32 bits?

1 Answers

It cannot simply increment it by the size of a "typical" instruction because there is no such thing as a "typically-sized" instruction in the x86 architecture. Instructions have all kinds of weird, varying sizes, as well as the possibility for various optional prefixes. (Although there is an upper bound: instructions can only consist of at most 15 bytes.)

Although many popular RISC processors use a fixed-width encoding for instructions (Alpha, MIPS, and PowerPC all have fixed-size 32-bit instructions, while Itanium has fixed-size 41-bit instructions), Intel x86 uses a variable-width encoding, primarily for historical reasons. It is a very complicated ISA!

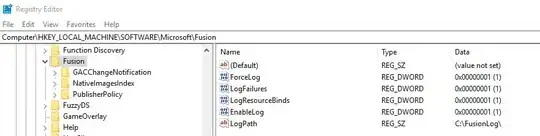

(Image taken from Igor Kholodov's lecture notes: http://www.c-jump.com/CIS77/CPU/x86/lecture.html)

Thus, the processor has to have internal logic that updates the instruction pointer (IP) as part of its instruction decoding process. It fetches the instruction, decodes it, and increments the instruction pointer by the actual size of the decoded instruction. (That is, from the programmer's high-level perspective. Internally, things are even more complicated, thanks to speculative execution.)

Because instruction decoding is so complicated, a lot of silicon has to be devoted to doing this. On the low-power Atom processor, around 20% of the total power consumption comes just from decoding instructions. However, there is at least one benefit to this complexity: increased instruction density. Variable-length instruction encoding means that certain, commonly-used instructions can be encoded using only a few bytes, and therefore take up very little space in the instruction cache. So you have a classic engineering trade-off where, while the instruction decoder is larger and more complicated, the instruction cache can be made smaller and therefore cheaper.

Note that the instruction pointer is never decremented in normal, "straight-line" decoding. Unlike the stack, the instruction stream grows upward in memory. A decrement would only happen as a result of a branch, which your question explicitly put off-limits. But I'll break the rules and point out that, when a branch is executed (e.g., via an unconditional jmp, a conditional jump, or a call), the instruction pointer is explicitly changed to match the target of the branch.

- 239,200

- 50

- 490

- 574

-

Ok, I only included decrement because for all I know it could have run sequentially but downward instead of incrementing. Not as a branching sorry about that part. So then It increments basically the size of the opcode and it's operands. – marshal craft Dec 21 '16 at 20:50

-

Right, it has to increment the *exact* size of the instruction. It can't just guess. Unlike some popular RISC architectures, where all instructions have a fixed length, x86 instructions have wildly varying lengths. – Cody Gray - on strike Dec 21 '16 at 20:51

-

Also are you sure that part wouldn't be something that the assembler handles? Like the instruction when encoded by the assembler is then a 32 bit word allowing 4 million and something possible opcodes. Then reduced so that operands can be bits in the 32 bit word depending on the opcode. Then if that were the case it would be a simple matter to IP + 1 to next instruction. – marshal craft Dec 21 '16 at 20:54

-

If the designers had decided to use a fixed-width encoding for instructions, then yes, this would have been possible. It would make decoding *significantly* simpler, and would therefore require a lot less silicon devoted to it. But no, that isn't how x86 works, mainly for historical reasons. Each instruction in the stream can and often does have a different length, up to a maximum of 15 bytes. – Cody Gray - on strike Dec 21 '16 at 20:56

-

@marshalcraft: that's exactly how most fixed-width instruction sets work. Some opcodes use most of the bits for operands, while others use more of the bits to select between different opcodes that don't need as many operand bits. AVR is a good example of this. 16-bit instructions, with 32 registers of 8 bits each (some instructions can only use the upper 16 registers, because they only use 4 bits to encode the register). The instruction-set is pretty small, and the docs show which bits mean what in the encoding. e.g. [SBR](http://www.atmel.com/webdoc/avrassembler/avrassembler.wb_SBR.html) – Peter Cordes Dec 21 '16 at 21:24

-

Ok thanks both of you. Also what about alignment as far as istructions, should they be aligned (padded) so that next instruction starts at "integer" increments of the IP or no? Reason I ask this stuff is for spi flash lay out for instructions after reset vector at 0xFFFFFFF0. – marshal craft Dec 21 '16 at 21:30

-

@marshalcraft: no, you should definitely *not* insert a lot of NOPs into the instruction stream, except maybe to align very-frequently-used branch targets to 16B or something (with an `align 16` directive). But usually you don't even need to do that, with the most recent CPUs. x86 CPUs can't assume that instructions will start at any kind of alignment, and aren't optimized to benefit from that at all (except when fetching from a new location after a jump: fetch happens in naturally-aligned blocks to feed a queue for the decoders.) – Peter Cordes Dec 21 '16 at 22:40

-

@marshalcraft: For more about this, see http://agner.org/optimize/. Also other links in http://stackoverflow.com/tags/x86/info. – Peter Cordes Dec 21 '16 at 22:40

-

@peter Is there a specific reference you know off the top of your head for the claim that alignment of frequently-used branch targets is not beneficial "with the most recent CPUs"? As far as I know, 16-byte alignment is still a good idea for precisely the reasons you give in the last part of your comment, but that knowledge may be out of date with the very newest of architectures. The newest thing I have around here is a Sandy Bridge. – Cody Gray - on strike Dec 22 '16 at 04:15

-

@CodyGray: if it's hot in uop cache, I think it's irrelevant. So generally it doesn't matter for loop branches. For AMD, it probably still matters. You will see perf differences, but I think mostly from branches aliasing in the branch predictor differently when you change the alignment of everything. (i.e. it's the alignment of branch instructions relative to each other that matters for that, not branch *targets*.) – Peter Cordes Dec 22 '16 at 07:24

-

Since you have a SnB, can you do a frontend-throughput experiment? We have data on non-multiple-of-4 uop loops for HSW and SKL, but it doesn't match what I saw in more limited experiments on SnB, before a bad BIOS update bricked the DZ68DB mobo (thanks, Intel). [@Beeonrope has a test program on this question](http://stackoverflow.com/questions/39311872/is-performance-reduced-when-executing-loops-whose-uop-count-is-not-a-multiple-of), which uses Linux `perf`. If you don't have Linux on your SnB, even just a simple manual test of maybe 7, 8, and 9 uop loops would be really interesting. – Peter Cordes Dec 22 '16 at 07:30

-

@peter Okay, I'm game. I didn't have Linux installed, but I just set up Mint in a VM. I've got all the build tools and can compile successfully. I tried to install perf using `apt-get install linux-tools-common linux-tools-generic`, but when I run BeeOnRope's script, it seems that perf was not correctly installed. I get a screenful of errors saying "invalid or unsupported event: cycles:u,instructions:u,cpu/event=0xa8,umask=0x1,..." and providing usage information. I figured it'd be best to stick with the same test code, but I'm not a competent Linux user. What else do I need to make perf work? – Cody Gray - on strike Dec 22 '16 at 10:40

-

@CodyGray: IDK if hardware performance counters work in a VM. `linux-tools-generic` should have pulled in everything you need. – Peter Cordes Dec 22 '16 at 10:48

-

@CodyGray: In `dmesg | less` (kernel log messages), search for the kernel detecting the hardware (i.e. type `/PMU` [return]). On my system, there's a line that says: `Performance Events: PEBS fmt3+, Skylake events, 32-deep LBR, full-width counters, Intel PMU driver.`... (Just got a new desktop, i7-6700k with 16G of DDR4-2666. Everything is a *lot* faster than on the Core2Duo I reverted to after bricking my SnB :) – Peter Cordes Dec 22 '16 at 10:50

-

Hmm, the logs say "unsupported p6 CPU model 42 no PMU driver". The line right above though does successfully detect a Core i7-2600. Strange. I have VT-x enabled, so the hypervisor should be making this information available to the guest. I've successfully used V-Tune and other profilers in VMs. In fact, I do all my development in VMs! Well, I'll keep playing around to see what went wrong here, or perhaps look into adapting the code for an environment I'm more familiar with. Thanks, @Peter – Cody Gray - on strike Dec 22 '16 at 10:56

-

@CodyGray: bedtime for me, but if you're confident that your VM does correctly expose the PMU, then try just googling that error message. Maybe Mint is weird. Or try @iwill's Linux PMU driver (linked on the same SO question, I think). It's a kernel module that lets user-space code config the PMU and then read it directly. So it's lighter-weight than what the Linux `perf` API provides. (The kernel side of `perf` virtualizes the PMU counters so a process can count its own cycles even across context-switches and CPU migrations, instead of just everything on one core.) – Peter Cordes Dec 22 '16 at 11:05

-

If you get stuck, just try a couple small loops in your normal profiling environment to see what happens, and if it's different from what we see on HSW/SKL. e.g. a 9 uop loop might run at one per 3 cycles, or at one per 2.25 cycles. Should be easy to see and not dependent on how you measure it, just a pure front-end-throughput test. The main advantage to using Linux here is that @Bee already wrote a script that produces results in a format he can turn into graphs like for HSW and SKL. – Peter Cordes Dec 22 '16 at 11:11